As long as there have been vaccinations, there has been an antivaccine movement, and as long as there has been an antivaccine movement, there have been parents who refuse to vaccinate. In a past that encompasses the childhood of my parents, polio was paralyzing and killing children in large numbers in yearly epidemics, the fear of which led to the closure of public pools every summer. In such an environment, the new polio vaccine introduced by Jonas Salk in the mid-1950s wasn’t a hard sell. In fact, satisfying the initial demand for it was the problem, not parents refusing to vaccinate their children. Since then, more and more vaccines have been developed to protect more and more children from more and more diseases, to the point where the incidences of most vaccine-preventable diseases is so low that, unlike 60 years ago, most parents today have never seen a case or even known other parents whose child suffered from a case. Even as recently as the 1980s, Haemophilus influenza type B was a dread disease that could cause meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and death. Since the introduction of the the Hib vaccine a mere quarter century ago, Hib has been virtually eliminated. Most pediatricians in residency now have never seen a case.

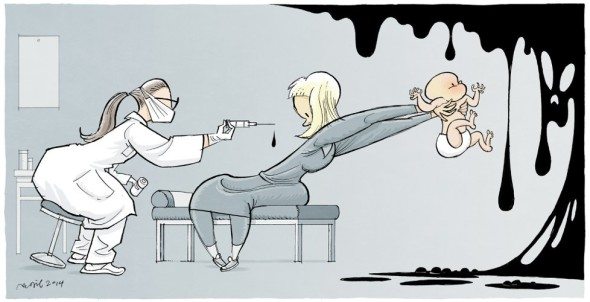

As much of a cliche as it is to say so, unfortunately vaccination has been a victim of its own success, at least in developed countries. Parents no longer fear the diseases childhood vaccines protect against, which makes it easy for antivaccine activists to provide what I like to call “misinformed consent,” by spreading misinformation that vastly exaggerates the risk of vaccines compared to the benefit of vaccinating. Basically, parents who believe the misinformation conclude, based on a warped view of the risk-benefit ratio of vaccines, that not vaccinating is safer. Add to the mix fear mongering against the MMR based on Andrew Wakefield and his dubious 1998 case series that popularized the then-recent idea that vaccines cause autism, and it’s no wonder that parents decide that not vaccinating is safer than vaccinating. If you believe the misinformation, it’s not an entirely unreasonable conclusion. Then add to that the easy availability of “personal belief exemptions” to school vaccine mandates in many states, which include anything from religious exemptions to parents just signing a form that says they are “personally opposed” to vaccination, and it isn’t a huge surprise that vaccine uptake has fallen in some areas to the point where outbreaks can occur. It was happening in California and my own state of Michigan.

The question then becomes: What to do about it? This question always brings up hard questions about how far the state should go to encourage vaccination, how many parents are vaccine-averse or even outright antivaccine, and the reasons why parents are vaccine-averse or antivaccine. This week, Medscape published its Vaccine Acceptance Report for 2016, which looks at some of these issues.

Vaccine acceptance: The lay of the land

Early in the story, Medscape notes correctly:

The personal and public health impact of vaccine hesitancy, if it culminates in refusal, is substantial. Parents offer many justifications for declining vaccines for their children, and traditionally have not been easily persuaded by statistics about a vaccine’s safety and efficacy, or horror stories about children who developed a vaccine-preventable disease. The burden on clinical practice in terms of time alone is significant, and providers must also grapple with such questions as how to provide quality pediatric care to unvaccinated children, how to protect other patients in the practice, and how to protect their own liability for any poor outcomes resulting from continuing to provide care to unvaccinated children.

The reasons behind vaccine hesitancy or refusal range from religious objections to personal beliefs, safety concerns, a preference for “natural” immunity, and a lack of accurate information about vaccines from a trusted source.

In response to this problem, Medscape administered a survey to health care professionals. 1,551 physicians, nurse practitioners, and physicians assistants in pediatrics, family medicine, and public health who worked in a practice setting where vaccines were administered to patients younger than 18 years were surveyed. Wherever possible, Medscape compared its results to a similar survey it conducted in 2015 in order to identify trends in vaccine hesitancy, refusal, or acceptance. Of course, one problem with this survey is that it’s just of health care professionals; in essence, it only tells one aspect of the story and relates the impressions that health care providers on the front line have regarding vaccine refusal. That means that the reasons for vaccine refusal that are related are only what parents tell health care practitioners, which might or might not be the real reasons behind vaccine hesitancy or refusal.

One piece of good news is that the clinicians surveyed don’t perceive an increase in vaccine refusal and hesitancy. Between 44-46% of clinicians perceive more acceptance of children’s vaccines in general, children’s measles vaccines, and the recommended vaccine schedule, while 42%-47% perceived no change in these same metrics. Only 9-14% perceived that these metrics have gotten worse since last year. This is encouraging, but it is only a perception. Whether it is an accurate reflection of what is going on is impossible to say. Similarly, whether the respondents are correct in their perceptions as to why vaccine hesitancy has decreased is impossible to say, but majorities respondents perceived that there has been more concern about infectious disease and more fear of children contracting vaccine-preventable diseases. Minorities were concerned that their children were denied admission to school, day care, or camp because they weren’t fully vaccinated.

Some of the comments by respondents to this question on the survey included attributing the perceived increasing acceptance of vaccines to:

- Changing attitudes in the lay press—less glorifying and more scrutiny of vaccine refusers/press finally coming down negatively on vaccine refusers.

- State laws removing philosophical exemptions for vaccines.

- Taking more time to address all of the parents’ concerns about vaccines.

- A new policy to dismiss vaccine refusers from practice

I’ve discussed the first one before from time to time, as I, too, have perceived a change in the attitude of the lay press over the last five years or so. Back in the day, when I first started blogging and paying attention to the antivaccine movement, a staple of my blogging was the examination of news reports by clueless journalists who treated vaccine stories and the idea that vaccines cause autism like any other issue, in which there had to be (at least) two sides. So for every quote by a vaccine advocate or pro-science advocate like Paul Offit, there would almost always be a countering quote by someone on the “other” side like Jenny McCarthy, Barbara Loe Fisher, or even Andrew Wakefield. Indeed, from time to time there were even very flattering profiles of Andrew Wakefield in press. Unfortunately, back then, the material for this sort of post far exceeded even my ability to cover all the articles I came across every week showing false balance. It was false balance, too, because the two viewpoints are not even close when it comes to scientific evidence for them. Billions of doses of vaccines have been administered with very few serious adverse events, while a veritable mountain of scientific studies attest to the safety and efficacy of vaccines. On the antivaccine side, there are anecdotes, confusing correlation with causation, and crappy studies and case series by the likes of Andrew Wakefield, Mark and David Geier, Christopher Shaw, Stephanie Seneff, and other antivaccine physicians, scientists, and scientist wannabes.

Then, beginning around five or six years ago, I started to notice a change. Fewer and fewer articles in the mainstream press exhibited what I considered to be false balance. I can’t quantify it, and maybe I’m suffering from confirmation bias, but it seems unmistakable to me. I also noticed a new shorthand for dismissing antivaccine views: Mentioning Andrew Wakefield, how he lost his UK medical license, and his fraudulent 1998 Lancet case series. Yes, it seems to me that the discrediting of Andrew Wakefield by the UK General Medical Council and by The Lancet’s retraction of his 1998 case series did far more to reverse the sad state of affairs in health reporting about vaccines than all the studies finding no link between vaccines and autism. I wish that it weren’t so, because I like to believe that people can be persuaded by scientific evidence, but we know that that’s not the primary way minds are changed. Anecdotes, stories, and statements from trusted people are far more effective, which is why I’ve resigned myself to this development and even sometimes use Andrew Wakefield as shorthand for discredited antivaccine beliefs myself. I would prefer not to, but at least this shorthand, besides being effective, has the added bonus of being true.

In fact, disconfirming data can even backfire and harden positions. There’s even a name for this phenomenon, disconfirmation bias, in which we humans tend to expend disproportionate energy trying to refute views and arguments with which we strongly disagree. There’s a related phenomenon known as the backfire effect, in which challenging a person’s deepest convictions with disconfirming evidence results not in the changing of that person’s mind but the strengthening of those beliefs. The process through which people manifest the backfire effect is sometimes called motivated reasoning, in which we are very good at finding facts and evidence that support our preexisting point of view. The more educated a person is, the better he is at motivated reasoning, which is why the most vocal antivaccine activists are so frequently highly educated and affluent.

Of course, we’re talking here about deeply held beliefs. This would describe what I like to call diehard antivaccinationists and the leaders of the antivaccine movement. They are notoriously difficult to persuade, and it’s rare that any of them flips to accepting the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Most parents who express concerns about vaccines are much less certain. Antivaccine beliefs are not deeply held; so the potential to reach them with evidence is there. More importantly, from my perspective, it is critical to keep the antivaccine misinformation spewed by the diehards (who can’t be persuaded) from influencing those susceptible to their message.

But what about vaccine refusers?

Vaccine refusal: The lay of the land

Medscape asked respondents who perceive that vaccine refusal is increasingly a problem what reasons they’ve heard from families. Here are the reasons, ranked from most common to least:

- Fear of connection to autism spectrum disorder

- Concerns about added ingredients in vaccines

- Worry child will suffer other complications from vaccine

- Worries about “overwhelming” infant’s immune system

- Distrust of pharmaceutical industry

- Believe child will get illness from vaccine

- Pain/stress of multiple injections for child

- Believe naturally acquired immunity is preferable

- Religious or political belief

- Doubt about vaccine efficacy

- Cost/lack of insurance coverage for vaccines

Note that the last concern was noted by only 8% of respondents.

Respondents also mentioned these reasons:

- Vaccines are not safe

- Worries about future repercussions of vaccines

- Diseases to be prevented are not that bad (or, as I like to call it, the Brady Bunch fallacy)

- Too many antigens given at once

- Fear that vaccines are a government plot

You’ll also note that every single one of the concerns that can be addressed with evidence has been discussed on this blog at one time or another. The evidence is clear: Vaccines do not contribute to autism. The concern about vaccine ingredients is one that I’ve dubbed the “toxins gambit” because, although there are chemicals such as formaldehyde in vaccines, they are present in such trace quantities as to be safe. Indeed, the amount of formaldehyde in infant vaccines is much smaller than the amount of formaldehyde circulating in the infant’s bloodstream from normal metabolic processes that generate it. “Natural immunity” might be more long lasting for some vaccine-preventable diseases, but the huge downside to natural immunity is that the child has to suffer the disease, with all its attendant suffering, morbidity, and even potential risk of death to achieve it. Worse, in the case of measles, “natural immunity” involves a suppression of the immune system that leaves children more susceptible to other diseases and results in increased mortality in children who have had the measles, an effect lasting up to three years post-infection. In other words, in the case of measles, at least, the benefits of the vaccine go beyond measles.

One issue that we who advocate vaccines probably don’t pay enough attention to is parental concern over the pain and stress of multiple vaccinations. That concern could be fairly easily overcome when it’s just one shot at a visit, but when a child gets two, three, or even more shots in a single visit, it can trigger a very deep protective instinct in parents that can cause a great deal of distress and lead them to start to wonder if all these shots are really necessary. Alice Dreger, who is pro-vaccine (although she has an unfortunate and irritating penchant for portraying vaccine advocates as frenzied self-righteous zealots, was honest enough to talk about her experience with this instinct in herself:

My maternal instinct was riled with every new round of shots and cries and tears: I remembered one particular visit to our paediatrician when my gut instinct had a sharp argument with my brain. I can’t even remember what the vaccine was; I just remember that Gut was yelling, “Enough already! Stand between our baby and that needle!” Trying to stay calm, Brain answered: “Vaccines are safe, and necessary not just for our baby’s health but for the health of those around him, especially children more vulnerable than him . . .”

Vaccines aren’t the only medical procedure performed on children that provokes this primal instinct, but it is by far the most common. Mild reactions, such as fever, after vaccination are not uncommon, as well. Such reactions, when they happen, only serve to fire up parental instincts even more next time. How physicians, nurses, and medical assistants deal with this natural anxiety in a parent who might be predisposed to become vaccine-averse or even vaccine refusers can make the difference.

It’s not all vaccines: HPV and flu vaccine resistance

Just as there are gradations of antivaccine views, from those who fervently believe that vaccines are ineffective and dangerous to those who have been influenced by antivaccine propaganda and fear that vaccines could harm their child, not all vaccines produce the same level of resistance. For instance, Medscape found that the vaccines most likely to be refused are the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine (Gardasil or Cervarix), the flu vaccine, and the MMR, while and the least likely to be refused is the Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) vaccine. It’s not surprising that the Hib vaccine is an easier sell, given how deadly the disease was up until the early 1990s, which is when the vaccine basically eliminated the disease except for a handful of cases every year. It’s also not surprising that resistance to the MMR vaccine remains high, given that even 18 years later Andrew Wakefield’s fraudulent study still reverberates, nor is it particularly surprising that flu vaccine resistance would be high given that people still have the mistaken impression that the flu is not a serious disease coupled with the variable and less than optimal efficacy of the flu vaccine.

I’m, however, somewhat surprised that the hepatitis B vaccine didn’t rank higher on this list, given the widespread perception of hepatitis B as a sexually transmitted disease and the frequent attacks of the birth dose of this vaccine by antivaccine zealots, but I’m not at all surprised that resistance to Gardasil is the highest because the HPV strains that cause cervical cancer are sexually transmitted. Not surprisingly, the reasons parents give are, in order of frequency from most frequent to least frequent:

- Parents did not perceive their child to be at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection

- Parents have concerns about the potential side effects of the HPV infection

- Parents voice concerns that the vaccine promotes sexual activity

- Parents believe that not vaccinating their children doesn’t harm anyone else.

- I’m unconvinced that the benefits outweigh the risks, so don’t promote as strongly as other vaccines

Fortunately, that last reason was only 7% of respondents, but that’s still rather high. It’s also very critical, as what this study probably didn’t pick up is this factor discussed by Medscape:

Other research supports the finding that provider ambivalence plays a role in HPV vaccine acceptance. Although most providers reported in a recent study that they usually discuss the HPV vaccine at the 11- or 12-year visit, only about 60% of pediatricians and family practice physicians strongly recommend the vaccine to parents. Without a strong recommendation from clinicians, it is unlikely that parents will be able to overcome other reservations about the vaccine, such as the fear that it will encourage sexual activity, concerns about safety, or relative unconcern about HPV disease.

In other words, if clinicians don’t, through action and word, let parents know that they consider the HPV vaccine to be very important, then why on earth would parents think it important enough to overcome their other concerns? These results also make it hard not to note that many US families are living in a fantasy world if they believe their teens are not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted disease, and it’s a myth that the HPV vaccine promotes promiscuity. Yet these mistaken impressions leave HPV vaccine uptake far below what it should be.

Strategies to counter vaccine hesitancy

Medscape also asked the clinicians it surveyed what strategies they found most effective at encouraging vaccination in families who hesitate or refuse vaccines. They found these strategies mentioned, in decreasing order of frequency:

- Providing evidence-based responses to concerns

- Telling parents you would/do vaccinate your children on the recommended schedule

- Providing info on potential morbidity/mortality of vaccine-preventable diseases

- Offering an alternative schedule

- Refusing to accept patients who won’t adhere to the recommended schedule

I note that, even though it’s the number one answer, “providing evidence-based responses to concerns” was only mentioned by 63%. Parents who are persuaded by evidence are almost certainly the ones least resistant to vaccines, given the backfire phenomenon. It’s not part of their world view or a deeply held belief. Notice, however, number two: Telling parents you would vaccinate. This is similar to a question I not infrequently am asked by patients with breast cancer: If I were your mother/wife/sister, what operation would you recommend? Again, the human connection and personal anecdotes are often more powerful than data.

As Medscape puts it:

Rather than a lack of information about vaccines, there is information overload from countless disparate sources.[14] Providing accurate information about vaccines to correct misinformation and misunderstandings is one of the most common strategies used by clinicians to increase parents’ confidence in vaccines. However, more than a few respondents were cynical about such strategies as sharing the science or telling “horror stories,” which, as one respondent said, “work rarely. Most antivaxxers are not influenced in any way.”

Again, just providing accurate information can be effective, but it is not enough, and it almost certainly won’t work with antivaccine parents, as opposed to just vaccine-hesitant parents. Other examples cited by Medscape are in line with this:

- Telling stories from early in my career when many current vaccines were not available and I watched children die from vaccine-preventable diseases

- Reminding parents that providers, too, want what is best for their children

- Explaining that healthy children must be vaccinated to protect more vulnerable children (kids with cancer, autoimmune diseases, transplant recipients, newborns) who can’t be vaccinated

Other suggestions included:

- Increase transparency about vaccines, better risk-benefit data, better tracking of adverse events

- Public service announcements with personal stories from families whose children’s lives have been affected by vaccine-preventable diseases

- More flexibility in alternative vaccine schedules

- Eliminate the vaccine court and restore the right of patients to sue vaccine manufacturers

- More patience from providers. Parents may be frightened and need a little space and understanding. Most will come around.

The last one is probably the most useful and likely to be effective, while health authorities already do public service announcements with personal stories of children harmed by vaccine-preventable diseases. The rest of these ideas range from being truly bad (eliminate the vaccine court) to being based on a misconception (increase transparency; vaccine safety data are already pretty darned transparent), to being medically a bad idea (more flexibility in alternative schedules).

Remember, it’s not just about vaccines

Overall, the 2016 Medscape survey probably does a decent job of capturing healthcare providers’ attitudes and perceptions regarding vaccine hesitancy. It doesn’t, however, look at the views of actual parents, and in my experience many providers are blissfully unaware of one thing: Whenever a parent refuses vaccines for her child, it’s almost always about more than just vaccines. I like to cite as an example a post from an antivaccine blog entitled Why don’t you vaccinate?, in which a father named Matt tries to answer that very question. The various reasons he gives are, of course, easily refutable and in fact have been refuted, but it’s worth looking at them anyway:

- It’s MY choice.

- Many vaccines are designed using aborted fetal tissue as a growth medium.

- Many vaccines contain foreign animal DNA.

- The ingredients in vaccines scare the crap out of me.

- Herd immunity does not exist.

- We’ve traded disease epidemics and natural immunity for neurological and auto-immune epidemics and artificial, temporary immunity.

- I don’t believe that vaccines eliminated diseases.

- The vaccines aren’t as effective as you’re led to believe.

- Financial incentives and conflicts of interest turn me off.

- Vaccine manufacturers are immune from any and all liability.

While it’s easy to laugh at the ridiculousness of some of Matt’s reasons, such as the claim that herd immunity doesn’t exist (it most certainly does), vaccines cause neurologic and autoimmune diseases (they do not), and how Matt “doesn’t believe” that vaccines eliminated any diseases (seriously, who cares what Matt “believes” about science, and I have two words for him: smallpox and, hopefully soon, polio), did you notice something about the reasons? Several of them have nothing to do with whether or not vaccines are safe and effective. For instance, the concern about whether vaccines are made in “aborted fetal tissue” is obviously incorrect, although 50 year old cell lines derived from aborted fetuses are used in the manufacture of some vaccines, which is a very different thing. However, concern about the source of cells used to make vaccines is not about whether these vaccines work or not; it’s about moral values, a world view, and deeply held beliefs, about whether vaccines will somehow sap and impurify our precious bodily DNA. The same is true about financial incentives and the belief that vaccine manufacturers are immune from all liability (they aren’t, of course). As exaggerated as these reasons are, they speak to a certain world view of which antivaccine beliefs are but a part.

Perhaps most important is what Matt lists at #1: It’s MY choice. Notice , in his original post, Matt starts with #10 and works his way to #1 in a countdown; so #1 is listed last. The buildup only emphasizes the importance of this reason, like a top 40 countdown does for the number one hit. Matt sees the requirement that he vaccinate his children if he wishes them to go to public school as an unacceptable affront to his own ability to choose. This is not surprising, given that Matt describes himself as a “a conservative millennial,” which means that politically he is opposed to anything he views as overweening governmental power; e.g., school vaccine mandates. It’s also a common reason among antivaccine activists and part of the reason that the appeal of the “health freedom” movement (which I like to characterize as the freedom of quacks to ply their quackery but its members see as the freedom to choose their own health care) is so potent. As you can see from his post, he’s also not bad at motivated reasoning, able to marshal information supporting his point of view while dismissing the much more powerful evidence refuting it.

When trying to persuade parents who are merely vaccine-averse but for whom vaccine hesitancy or refusal is not part of an overall world view that is inherent in their core beliefs, traditional methods of persuasion using evidence, trust between physician and patients’ parents, and anecdotes have a chance of working. When it comes to someone like Matt—or any of the bloggers at, for example Age of Autism or The Thinking Moms’ Revolution—such methods will almost certainly fail or even backfire. They remain the last, most difficult challenges. I fear that the Medscape survey, while providing me hope that the prevalence of vaccine refusal is probably decreasing (or at least probably not increasing), it doesn’t give me much confidence that most primary care physicians understand where antivaccine views come from.

Dealing with vaccine hesitancy and refusal David Gorski

No comments:

Post a Comment